It really is one of the best product names in Apple history: Vision is a description of a product, it is an aspiration for a use case, and it is a critique on the sort of society we are building, behind Apple’s leadership more than anyone else.

I am speaking, of course, about Apple’s new mixed reality headset that was announced at yesterday’s WWDC, with a planned ship date of early 2024, and a price of $3,499. I had the good fortune of using an Apple Vision in the context of a controlled demo — which is an important grain of salt, to be sure — and I found the experience extraordinary.

It’s far better than I expected, and I had high expectations.

— Ben Thompson (@benthompson) June 6, 2023

The high expectations came from the fact that not only was this product being built by Apple, the undisputed best hardware maker in the world, but also because I am, unlike many, relatively optimistic about VR. What surprised me is that Apple exceeded my expectations on both counts: the hardware and experience were better than I thought possible, and the potential for Vision is larger than I anticipated. The societal impacts, though, are much more complicated.

The Vision Product

VR + AR

I have, for as long as I have written about the space, highlighted the differences between VR (virtual reality) and AR (augmented reality). From a 2016 Update:

I think it’s useful to make a distinction between virtual and augmented reality. Just look at the names: “virtual” reality is about an immersive experience completely disconnected from one’s current reality, while “augmented” reality is about, well, augmenting the reality in which one is already present. This is more than a semantic distinction about different types of headsets: you can divide nearly all of consumer technology along this axis. Movies and videogames are about different realities; productivity software and devices like smartphones are about augmenting the present. Small wonder, then, that all of the big virtual reality announcements are expected to be video game and movie related.

Augmentation is more interesting: for the most part it seems that augmentation products are best suited as spokes around a hub; a car’s infotainment system, for example, is very much a device that is focused on the current reality of the car’s occupants, and as evinced by Ford’s announcement, the future here is to accommodate the smartphone. It’s the same story with watches and wearables generally, at least for now.

I highlight that timing reference because it’s worth remembering that smartphones were originally conceived of as a spoke around the PC hub; it turned out, though, that by virtue of their mobility — by being useful in more places, and thus capable of augmenting more experiences — smartphones displaced the PC as the hub. Thus, when thinking about the question of what might displace the smartphone, I suspect what we today think of a “spoke” will be a good place to start. And, I’d add, it’s why platform companies like Microsoft and Google have focused on augmented, not virtual, reality, and why the mysterious Magic Leap has raised well over a billion dollars to-date; always in your vision is even more compelling than always in your pocket (as is always on your wrist).

I’ll come back to that last paragraph later on; I don’t think it’s quite right, in part because Apple Vision shows that the first part of the excerpt wasn’t right either. Apple Vision is technically a VR device that experientially is an AR device, and it’s one of those solutions that, once you have experienced it, is so obviously the correct implementation that it’s hard to believe there was ever any other possible approach to the general concept of computerized glasses.

This reality — pun intended — hits you the moment you finish setting up the device, which includes not only fitting the headset to your head and adding a prescription set of lenses, if necessary, but also setting up eye tracking (which I will get to in a moment). Once you have jumped through those hoops you are suddenly back where you started: looking at the room you are in with shockingly full fidelity.

What is happening is that Apple Vision is utilizing some number of its 12 cameras to capture the outside world, and displaying them to the postage-stamp sized screens in front of your eyes in a way that makes you feel like you are wearing safety goggles: you’re looking through something, that isn’t exactly like total clarity but is of sufficiently high resolution and speed that there is no reason to think it’s not real.

The speed is essential: Apple claims that the threshold for your brain to notice any sort of delay in what you see and what your body expects you to see (which is what causes known VR issues like motion sickness) is 12 milliseconds, and that the Vision visual pipeline displays what it sees to your eyes in 12 milliseconds or less. This is particularly remarkable given that the time for the image sensor to capture and process what it is seeing is along the lines of 7~8 milliseconds, which is to say that the Vision is taking that captured image, processing it, and displaying it in front of your eyes in around 4 milliseconds.

This is, truly, something that only Apple could do, because this speed is function of two things: first, the Apple-designed R1 processor (Apple also designed part of the image sensor), and second, the integration with Apple’s software. Here is Mike Rockwell, who led the creation of the headset, explaining “visionOS”:

None of this advanced technology could come to life without a powerful operating system called “visionOS”. It’s built on the foundation of the decades of engineering innovation in macOS, iOS, and iPad OS. To that foundation we added a host of new capabilities to support the low latency requirements of spatial computing, such as a new real-time execution engine that guarantees performance-critical workloads, a dynamically foveated rendering pipeline that delivers maximum image quality to exactly where your eyes are looking for every single frame, a first-of-its-kind multi-app 3D engine that allows different apps to run simultaneously in the same simulation, and importantly, the existing application frameworks we’ve extended to natively support spatial experiences. visionOS is the first operating system designed from the ground up for spatial computing.

The key part here is the “real-time execution engine”; “real time” isn’t just a descriptor of the experience of using Vision Pro: it’s a term-of-art for a different kind of computing. Here’s how Wikipedia defines a real-time operating system:

A real-time operating system (RTOS) is an operating system (OS) for real-time computing applications that processes data and events that have critically defined time constraints. An RTOS is distinct from a time-sharing operating system, such as Unix, which manages the sharing of system resources with a scheduler, data buffers, or fixed task prioritization in a multitasking or multiprogramming environment. Processing time requirements need to be fully understood and bound rather than just kept as a minimum. All processing must occur within the defined constraints. Real-time operating systems are event-driven and preemptive, meaning the OS can monitor the relevant priority of competing tasks, and make changes to the task priority. Event-driven systems switch between tasks based on their priorities, while time-sharing systems switch the task based on clock interrupts.

Real-time operating systems are used in embedded systems for applications with critical functionality, like a car, for example: it’s ok to have an infotainment system that sometimes hangs or even crashes, in exchange for more flexibility and capability, but the software that actually operates the vehicle has to be reliable and unfailingly fast. This is, in broad strokes, one way to think about how visionOS works: while the user experience is a time-sharing operating system that is indeed a variation of iOS, and runs on the M2 chip, there is a subsystem that primarily operates the R1 chip that is real-time; this means that even if visionOS hangs or crashes, the outside world is still rendered under that magic 12 milliseconds.

This is, needless to say, the most meaningful manifestation yet of Apple’s ability to integrate hardware and software: while previously that integration manifested itself in a better user experience in the case of a smartphone, or a seemingly impossible combination of power and efficiency in the case of Apple Silicon laptops, in this case that integration makes possible the melding of VR and AR into a single Vision.

Mirrorless and Mixed Reality

In the early years of digital cameras there was bifurcation between consumer cameras that were fully digital, and high-end cameras that had a digital sensor behind a traditional reflex mirror that pushed actual light to an optical viewfinder. Then, in 2008, Panasonic released the G1, the first-ever mirrorless camera with an interchangeable lens system. The G1 had a viewfinder, but the viewfinder was in fact a screen.

This system was, at the beginning, dismissed by most high-end camera users: sure, a mirrorless system allowed for a simpler and smaller design, but there was no way a screen could ever compare to actually looking through the lens of the camera like you could with a reflex mirror. Fast forward to today, though, and nearly every camera on the market, including professional ones, are mirrorless: not only did those tiny screens get a lot better, brighter, and faster, but they also brought many advantages of their own, including the ability to see exactly what a photo would look like before you took it.

Mirrorless cameras were exactly what popped into my mind when the Vision Pro launched into that default screen I noted above, where I could effortlessly see my surroundings. The field of view was a bit limited on the edges, but when I actually brought up the application launcher, or was using an app or watching a video, the field of vision relative to an AR experience like a Hololens was positively astronomical. In other words, by making the experience all digital, the Vision Pro delivers an actually useful AR experience that makes the still massive technical challenges facing true AR seem irrelevant.

The payoff is the ability to then layer in digital experiences into your real-life environment: this can include productivity applications, photos and movies, conference calls, and whatever else developers might come up with, all of which can be used without losing your sense of place in the real world. To just take one small example, while using the Vision Pro, my phone kept buzzing with notifications; I simply took the phone out of my pocket, opened control center, and turned on do-not-disturb. What was remarkable only in retrospect is that I did all of that while technically being closed off to the world in virtual reality, but my experience was of simply glancing at the phone in my hand without even thinking about it.

Making everything digital pays off in other ways, as well; the demo included this dinosaur experience, where the dinosaur seems to enter the room:

The whole reason this works is because while the room feels real, it is in fact rendered digitally.

It remains to be seen how well this experience works in reverse: the Vision Pro includes “EyeSight”, which is Apple’s name for the front-facing display that shows your eyes to those around you. EyeSight wasn’t a part of the demo, so it remains to be seen if it is as creepy as it seems it might be: the goal, though, is the same: maintain a sense of place in the real world not by solving seemingly-impossible physics problems, but by simply making everything digital.

The User Interface

That the user’s eyes can be displayed on the outside of the Vision Pro is arguably a by-product of the technology that undergirds the Vision Pro’s user interface: what you are looking at is tracked by the Vision Pro, and when you want to take action on whatever you are looking at you simply touch your fingers together. Notably, your fingers don’t need to be extended into space: the entire time I used the Vision Pro my hands were simply resting in my lap, their movement tracked by the Vision Pro’s cameras.

It’s astounding how well this works, and how natural it feels. What is particularly surprising is how high-resolution this UI is; look at this crop of a still from Apple’s presentation:

The bar at the bottom of Photos is how you “grab” Photos to move it anywhere (literally); the small circle next to the bar is to close the app. On the left are various menu items unique to Photos. What is notable about these is how small they are: this isn’t a user interface like iOS or iPadOS that has to accommodate big blunt fingers; rather, visionOS’s eye tracking is so accurate that it can easily delineate the exact user interface element you are looking at, which again, you trigger by simply touching your fingers together. It’s extraordinary, and works extraordinarily well.

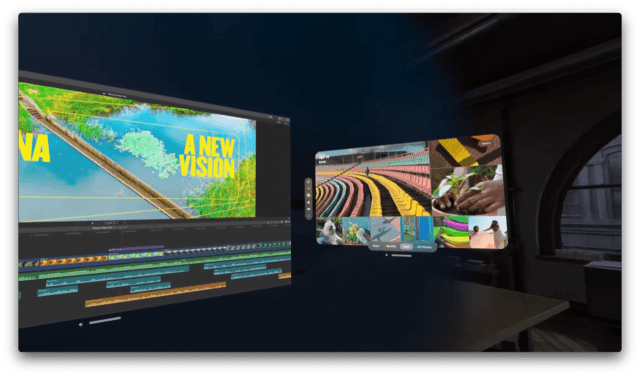

Of course you can also use a keyboard and trackpad, connected via Bluetooth, and you can also project a Mac into the Vision Pro; the full version of the above screenshot has a Mac running Final Cut Pro to the left of Photos:

I didn’t get the chance to try the Mac projection, but truthfully, while I went into this keynote the most excited about this capability, the native interface worked so well that I suspect I am going to prefer using native apps, even if those apps are also available for the Mac.

The Vision Aspiration

The Vision Pro as Novelty Device

An incredible product is one thing; the question on everyone’s mind, though, is what exactly is this useful for? Who has room for another device in their life, particularly one that costs $3,499?

This question is, more often than not, more important to the success of a product than the quality of the product itself. Apple’s own history of new products is an excellent example:

- The PC (including the Mac) brought computing to the masses for the first time; there was a massive amount of greenfield in people’s lives, and the product category was a massive success.

- The iPhone expanded computing from the desktop to every other part of a person’s life. It turns out that was an even larger opportunity than the desktop, and the product category was an even larger success.

- The iPad, in contrast to the Mac and iPhone, sort of sat in the middle, a fact that Steve Jobs noted when he introduced the product in 2010:

All of us use laptops and smartphones now. Everybody uses a laptop and/or a smartphone. And the question has arisen lately, is there room for a third category of device in the middle? Something that’s between a laptop and a smartphone. And of course we’ve pondered this question for years as well. The bar is pretty high. In order to create a new category of devices those devices are going to have to be far better at doing some key tasks. They’re going to have to be far better at doing some really important things, better than laptop, better than the smartphone.

Jobs went on to list a number of things he thought the iPad might be better at, including web browsing, email, viewing photos, watching videos, listening to music, playing games, and reading eBooks.

In truth, the only one of those categories that has truly taken off is watching video, particularly streaming services. That’s a pretty significant use case, to be sure, and the iPad is a successful product (and one whose potential use cases has been dramatically expanded by the Apple Pencil) that makes nearly as much revenue as the Mac, even though it dominates the tablet market to a much greater extent than the Mac does the PC market. At the same time, it’s not close to the iPhone, which makes sense: the iPad is a nice addition to one’s device collection, whereas an iPhone is essential.

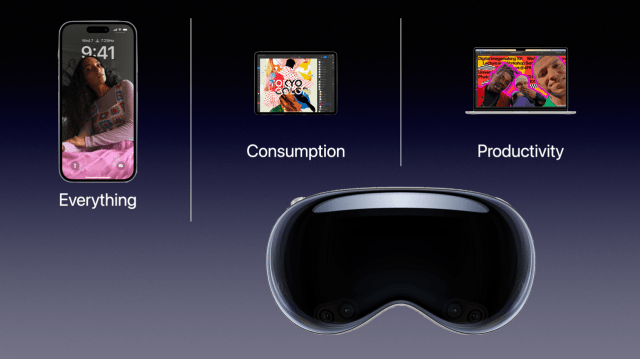

The critics are right that this will be Apple Vision’s challenge at the beginning: a lot of early buyers will probably be interested in the novelty value, or will be Apple super fans, and it’s reasonable to wonder if the Vision Pro might becomes the world’s most expensive paper weight. To use an updated version of Jobs’ slide:

Small wonder that Apple has reportedly pared its sales estimates to less than a million devices.

The Vision Pro and Productivity

As I noted above, I have been relatively optimistic about VR, in part because I believe the most compelling use case is for work. First, if a device actually makes someone more productive, it is far easier to justify the cost. Second, while it is a barrier to actually put on a headset — to go back to my VR/AR framing above, a headset is a destination device — work is a destination. I wrote in another Update in the context of Meta’s Horizon Workrooms:

The point of invoking the changes wrought by COVID, though, was to note that work is a destination, and its a destination that occupies a huge amount of our time. Of course when I wrote that skeptical article in 2018 a work destination was, for the vast majority of people, a physical space; suddenly, though, for millions of white collar workers in particular, it’s a virtual space. And, if work is already a virtual space, then suddenly virtual reality seems far more compelling. In other words, virtual reality may be much more important than previously thought because the vector by which it will become pervasive is not the consumer space (and gaming), but rather the enterprise space, particularly meetings.

Apple did discuss meetings in the Vision Pro, including a framework for personas — their word for avatars — that is used for Facetime and will be incorporated into upcoming Zoom, Teams, and Webex apps. What is much more compelling to me, though, is simply using a Vision Pro instead of a Mac (or in conjunction with one, by projecting the screen).

At the risk of over-indexing on my own experience, I am a huge fan of multiple monitors: I have four at my desk, and it is frustrating to be on the road right now typing this on a laptop screen. I would absolutely pay for a device to have a huge workspace with me anywhere I go, and while I will reserve judgment until I actually use a Vision Pro, I could see it being better at my desk as well.

I have tried this with the Quest, but the screen is too low of resolution to work comfortably, the user interface is a bit clunky, and the immersion is too complete: it’s hard to even drink coffee with it on. Oh, and the battery life isn’t nearly good enough. Vision Pro, though, solves all of these problems: the resolution is excellent, I already raved about the user interface, and critically, you can still see around you and interact with objects and people. Moreover, this is where the external battery solution is an advantage, given that you can easily plug the battery pack into a charger and use the headset all day (and, assuming Apple’s real-time rendering holds up, you won’t get motion sickness).1

Again, I’m already biased on this point, given both my prediction and personal workflow, but if the Vision Pro is a success, I think that an important part of its market will to at first be used alongside a Mac, and as the native app ecosystem develops, to be used in place of one.

To put it even more strongly, the Vision Pro is, I suspect, the future of the Mac.

Vision and the iPad

The larger Vision Pro opportunity is to move in on the iPad and to become the ultimate consumption device:

The keynote highlighted the movie watching experience of the Vision Pro, and it is excellent and immersive. Of course it isn’t, in the end, that much different than having an excellent TV in a dark room.

What was much more compelling were a series of immersive video experiences that Apple did not show in the keynote. The most striking to me were, unsurprisingly, sports. There was one clip of an NBA basketball game that was incredibly realistic: the game clip was shot from the baseline, and as someone who has had the good fortune to sit courtside, it felt exactly the same, and, it must be said, much more immersive than similar experiences on the Quest.

It turns out that one reason for the immersion is that Apple actually created its own cameras to capture the game using its new Apple Immersive Video Format. The company was fairly mum about how it planned to make those cameras and its format more widely available, but I am completely serious when I say that I would pay the NBA thousands of dollars to get a season pass to watch games captured in this way. Yes, that’s a crazy statement to make, but courtside seats cost that much or more, and that 10-second clip was shockingly close to the real thing.

What is fascinating is that such a season pass should, in my estimation, look very different from a traditional TV broadcast, what with its multiple camera angles, announcers, scoreboard slug, etc. I wouldn’t want any of that: if I want to see the score, I can simply look up at the scoreboard as if I’m in the stadium; the sounds are provided by the crowd and PA announcer. To put it another way, the Apple Immersive Video Format, to a far greater extent than I thought possible, truly makes you feel like you are in a different place.

Again, though, this was a 10 second clip (there was another one for a baseball game, shot from the home team’s dugout, that was equally compelling). There is a major chicken-and-egg issue in terms of producing content that actually delivers this experience, which is probably why the keynote most focused on 2D video. That, by extension, means it is harder to justify buying a Vision Pro for consumption purposes. The experience is so compelling though, that I suspect this problem will be solved eventually, at which point the addressable market isn’t just the Mac, but also the iPad.

What is left in place in this vision is the iPhone: I think that smartphones are the pinnacle in terms of computing, which is to say that the Vision Pro makes sense everywhere the iPhone doesn’t.

The Vision Critique

I recognize how absurdly positive and optimistic this Article is about the Vision Pro, but it really does feel like the future. That future, though, is going to take time: I suspect there will be a slow burn, particularly when it comes to replacing product categories like the Mac or especially the iPad.

Moreover, I didn’t even get into one of the features Apple is touting most highly, which is the ability of the Vision Pro to take “pictures” — memories, really — of moments in time and render them in a way that feels incredibly intimate and vivid.

One of the issues is the fact that recording those memories does, for now, entail wearing the Vision Pro in the first place, which is going to be really awkward! Consider this video of a girl’s birthday party:

It’s going to seem pretty weird when dad is wearing a headset as his daughter blows out birthday candles; perhaps this problem will be fixed by a separate line of standalone cameras that capture photos in the Apple Immersive Video Format, which is another way to say that this is a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem.

What was far more striking, though, was how the consumption of this video was presented in the keynote:

Note the empty house: what happened to the kids? Indeed, Apple actually went back to this clip while summarizing the keynote, and the line “for reliving memories” struck me as incredibly sad:

I’ll be honest: what this looked like to me was a divorced dad, alone at home with his Vision Pro, perhaps because his wife was irritated at the extent to which he got lost in his own virtual experience. That certainly puts a different spin on Apple’s proud declaration that the Vision Pro is “The Most Advanced Personal Electronics Device Ever”.

Indeed, this, even more than the iPhone, is the true personal computer. Yes, there are affordances like mixed reality and EyeSight to interact with those around you, but at the end of the day the Vision Pro is a solitary experience.

That, though, is the trend: long-time readers know that I have long bemoaned that it was the desktop computer that was christened the “personal” computer, given that the iPhone is much more personal, but now even the iPhone has been eclipsed. The arc of technology, in large part led by Apple, is for ever more personal experiences, and I’m not sure it’s an accident that that trend is happening at the same time as a society-wide trend away from family formation and towards an increase in loneliness.

This, I would note, is where the most interesting comparisons to Meta’s Quest efforts lie. The unfortunate reality for Meta is that they seem completely out-classed on the hardware front. Yes, Apple is working with a 7x advantage in price, which certainly contributes to things like superior resolution, but that bit about the deep integration between Apple’s own silicon and its custom-made operating system are going to very difficult to replicate for a company that has (correctly) committed to an Android-based OS and a Qualcomm-designed chip.

What is more striking, though, is the extent to which Apple is leaning into a personal computing experience, whereas Meta, as you would expect, is focused on social. I do think that presence is a real thing, and incredibly compelling, but achieving presence depends on your network also having VR devices, which makes Meta’s goals that much more difficult to achieve. Apple, meanwhile, isn’t even bothering with presence: even its Facetime integration was with an avatar in a window, leaning into the fact you are apart, whereas Meta wants you to feel like you are together.

In other words, there is actually a reason to hope that Meta might win: it seems like we could all do with more connectedness, and less isolation with incredible immersive experiences to dull the pain of loneliness. One wonders, though, if Meta is in fact fighting Apple not just on hardware, but on the overall trend of society; to put it another way, bullishness about the Vision Pro may in fact be a function of being bearish about our capability to meaningfully connect.