Penn State has always been a usurper, at least to me.

In 1984 the Supreme Court ruled that the NCAA’s attempt to control individual universities’ college football TV rights was an illegal restraint on trade; while the lawsuit was instigated by the University of Oklahoma, it was conferences that were the biggest beneficiary, as it simply made more sense to negotiate TV rights as a collective of similarly situated schools. This was a problem for independent Penn State; its traditional rivals like Pitt, Syracuse, and Boston College joined the basketball-focused Big East, leaving the football power to make overtures to the Big Ten.

The 1990 announcement that Penn State was joining the conference was a controversial one within the Big Ten itself. A fair number of the conference’s athletic directors were opposed to the move, and most of the coaches (it is university presidents that make the decision, and even there Penn State only received the minimum 7 votes in favor); I was a 10 year-old sports fan of a then-decrepit football team in Wisconsin that had nothing going for it other than Big Ten pride, and resented the idea that Penn State was going to come in and potentially dominate the conference.

It all feels quite quaint here in 2022, and not just because Wisconsin has had more football success than Penn State; the Big Ten added Nebraska in 2011, and Maryland and Rutgers in 2014, in both cases setting off seismic shifts in the college landscape. Both expansions made sense on the edges, both figuratively and literally: Nebraska was a traditional football power neighboring Iowa that, more importantly, gave the conference the 12 teams necessary to stage a lucrative conference championship game. Maryland and Rutgers bordered Pennsylvania — Penn State was a well-established member of the Big Ten by this point, in practice if not in my mind — and, more importantly, brought the Washington D.C. and New York City markets to the Big Ten’s groundbreaking cable TV network.

It is the latest expansion announcement, though, that blows apart the entire concept of a regional conference founded on geographic rivalries: UCLA and USC will join the Big Ten in 2024. They are not, needless to say, in a Big Ten border state:

That, though, very much fits the reality of 2022: geography doesn’t matter, but attention does, and after the SEC grabbed Texas and Oklahoma last year, the two Los Angeles universities represented the two biggest programs not yet in the two biggest conferences. As for the timing, it’s all about TV: the Big Ten is in the middle of negotiating new rights packages this summer, while the Pac-12’s rights package ends in 2024. One thing is for sure: everyone in college sports, particularly those who, like 10-year-old me, value tradition, know exactly who to blame:

Reminder that Big Ten expansion in ’22 was entirely driven by Fox, just as SEC expansion in ’21 was entirely driven by ESPN. They are the grandmasters calling the shots behind the scenes.

(This message will repeat tomorrow morning)

— Jon Wilner (@wilnerhotline) July 2, 2022

This appears to be true as far as the mechanics of the Big Ten’s expansion: Fox reportedly instigated the UCLA and USC talks with the Big Ten. Figuring out why it was Fox, though — and ESPN with the SEC — exculpates both networks from ultimate responsibility.

A Brief History of TV

TV’s origins are, unsurprisingly, in radio: thanks to the magic of over-the-air broadcasting a radio station could deliver audio to anyone in its geographic area with a compatible listening device. Originally all of said audio was generated at the radio station, but given that most people wanted to listen to similar things, it made sense to link stations together and broadcast the same content all at once. In 1928 NBC became the first coast-to-coast radio network, linking together radio stations with phone lines; those stations weren’t owned by NBC, but were rather affiliates: local owners would actually operate the stations and sell local ads, and pay a fee to NBC for content that, because it was funded by stations across the country, was far more compelling than anything that could be produced locally.

TV followed the same path: thanks to the increased cost of producing video relative to audio, the economic logic of centralized content production was even more compelling (as were the proceeds from selling ads nationally). The content was more compelling as well, leading to further innovation in distribution, specifically the advent of cable that I wrote about earlier this year. That new distribution led to further innovation in content: new networks were created specifically for cable, even though cable had originally been created to help people receive over-the-air broadcasts.

In fact, new cable networks were so compelling that local broadcast stations (particularly those unaffiliated with the national networks) were worried about losing carriage, leading the FCC to institute “must-carry” rules that compelled cable networks to carry local broadcast networks for free. However, in the 1980s must-carry rules were ruled by a federal Appeals Court to be an infringement on the cable carriers’ First Amendment rights, threatening local broadcast networks that depended on the rules for access to an increasingly large percentage of homes.

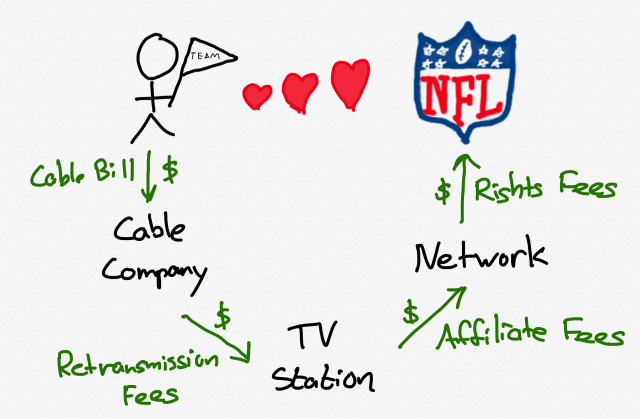

This ruling was an impetus for the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, which among other provisions, gave local broadcast stations the choice between must-carry status or charging retransmission fees; if the station chose the latter, then they forewent the former. This led to a clear bifurcation in broadcast channels: cheap and mostly local programming chose must-carry, while stations with the most desirable programming — which per the aforementioned point, were affiliated with national networks — chose the latter. Those national networks took notice: a significant part of the increase in cable fees over the last thirty years has been driven by national networks increasing the fees they charge affiliates for programming; those affiliates recoup those fees by increasing their retransmission fees (cable companies, for their part, continue to break out these fees on bills — my “Broadcast TV Surcharge” in Wisconsin is $21/month).

Local stations originally pushed back against this shift, de-affiliating with networks that pushed too hard. The problem, though, came back to content: networks had everything from popular sitcoms and dramas to national news to late night talk shows. The most important bit of content, though, was sports. Moreover, the importance of sports has only increased as those other content offerings have been unbundled by the Internet: streaming services have sitcoms and dramas, websites have all of the news you could ever want to consume, and social media provides all kinds of comedy and commentary; the one exception to Internet disruption are live games between teams you care about.

Fox’s Contrarian Bet

The importance of sports to ESPN is self-explanatory: the entire point of the network is to show games, particularly as its SportsCenter and talk show franchises have suffered from competition with the Internet. ESPN’s parent company, Disney, has jumped into this competition with both feet, launching Disney+ and taking a controlling stake in Hulu.

That controlling stake came from a deal that Disney announced in 2017: the company acquired the majority of 21st Century Fox, including: its film and television studios, most of its cable TV networks (including FX), a controlling stake in National Geographic, Star India, and the aforementioned stake in Hulu. Disney’s rationale was that it needed to beef up its content offerings to compete in streaming, which was clearly the future; traditional TV was, by implication, the past.

That left a newly spun-out Fox Corporation, which included the Fox broadcast network, Fox News, and Fox Sports (including the Fox Sports cable channels and Fox’s share in the Big Ten network); the nature of these channels signaled a completely different strategy than streaming. I wrote at the time in a Daily Update:

In that last sentence I actually put forth two distinct strategies: selling direct to consumers, and charging distributors significantly more. Both do depend on having differentiated content, which was the point of that Daily Update, but the similarities end there. To explain what I mean, this deal actually offers two great examples: if it goes through, that means Fox is pursuing the second strategy, and Disney the first.

Start with Fox: its news and sports divisions — particularly the former — are highly differentiated. That gives Fox significant pricing power with shrinking-but-still-very-large TV distributors. Moreover, given that both news and sports are heavily biased towards live viewing, they are also a good fit for advertising, which again, matches up with traditional TV distribution. What Fox would accomplish with this deal, then, is shedding a huge amount of that detritus I mentioned earlier: sure, more was better when there was only one distributor, but now that there is competition for viewer’s attention, filler is a drag on the content that actually gives negotiating leverage. Fox could come out of this deal with the same pricing power it has today but a vastly streamlined corporate structure and cost basis.

It’s a bet that has paid off: while Disney, like other streaming companies, enjoyed a huge run-up during the pandemic, it is Fox that today has the superior returns in its two years as an independent company:

Still, I think my original analysis was incomplete; Fox isn’t simply wringing more money out of a dying business model with a leaner corporate structure. Rather, it is driving the paid-TV business model to its logical endpoint: nothing but sports and news. That doesn’t mean, though, they are the biggest winner.

Sports Concentration

The foundation of Fox’s offering is the NFL, but it is an expensive offering: $2.025 billion per year for Sunday afternoon regular season games, playoffs, and the Super Bowl every four years. The NFL understands its position in the sports landscape very well — it has a monopoly on the professional version of America’s favorite sport — and it prices its rights accordingly, even as it is careful to spread its games across multiple networks:1

College football is America’s second favorite sport; it has also traditionally been a much more profitable one for the networks. CBS, for example, currently pays the SEC $55 million per year to broadcast the conference’s top games, which average over 6 million viewers per telecast; that is about a third of what CBS averages for NFL games, but at a fraction of the cost for rights. The relative cheapness of that deal is explained by the fact it was negotiated a decade ago, when the college football landscape was considerably more diffused:2

The SEC’s new deal looks a lot different: ESPN has exclusive rights to SEC football3 for $300 million per year. That increase is driven by the SEC’s dominance of college football, and corresponding national interest; that interest will be that much greater thanks to the addition of Texas and Oklahoma (which will almost certainly lead to an increase in rights fees). In short, sports are the biggest driver of pay-TV, which means it is essential to have the sports the most people want to watch; the SEC figures prominently in that regard.

Still, it is the Big Ten, based in the sports-obsessed Midwest, and filled with massive public universities churning out interested alumni who live all over the country, that is the most attractive of all; even before this expansion the conference was rumored to be seeking a deal for $1.1 billion/year. Add in the Los Angeles market and UCLA and USC fan bases and that number could end up even higher.

Blame Games

Put all of these pieces together, and the question of who exactly is responsible for college football’s conference upheavel gets a bit more complicated:

- Local TV stations charge ever higher retransmission fees to pay-TV operators because they have compelling content that subscribers demand.

- Networks charge ever higher affiliate fees to TV stations for that compelling content, extracting most (if not all) of those retransmission fees.

- The most compelling content is sports, especially as alternative content loses out to the Internet, and the most popular sport (the NFL) is governed by a single entity, allowing it to extract the greatest fees.

All of this extraction is a function of relative bargaining power that is ultimately derived from what fans want to see:

Given this, the logic of the Big Ten’s expansion into California is obvious: the more of an audience that the Big Ten can command, the more of the money flowing through that value chain it can extract. Sure, it’s not quite to the level of the NFL, but it’s the next closest thing. This is also the downside to Fox’s bet on live: while the company owns the content it produces on channels like Fox News, it has to buy sports rights, and it is the Big Ten that is determined to take its share, even if that means an expansion that otherwise makes no sense at all.

In other words, I think the tweet above has it backwards: Fox and ESPN are not “grandmasters calling the shots behind the scenes”; they are essential but ultimately replaceable parts in the movement of money from consumers to the entities that provide the content those consumers want.

Still, the tweet is instructive: perhaps the most essential role Fox and ESPN play for universities is taking the blame as the latter make more money than ever.

I wrote a follow-up to this Article in this Daily Update.