It’s been a bit of an anniversary celebration here at Stratechery HQ: it was just under a year ago that I had my first bout of COVID, which left me locked up in a Taiwanese quarantine facility for 18 days. Stuck with nothing to do on the weekends in particular I decided to watch the Australian Grand Prix Formula 1 race,1 and I was immediately hooked; I haven’t missed a race since.

This weekend, I got COVID again, but fortunately this was the same weekend that Netflix released the 5th season of “Drive to Survive”, its docuseries about Formula 1: I’ve sped-run through the “Drive to Survive is so cool” to “Drive to Survive is so unrealistic” to “Relax, ‘Drive to Survive’ is fun” cycle like Max Verstappen at Spa, so I was happy enough plowing through the entire season with a box of Kleenex for my runny nose (the Episode 2 team principal meeting was the obvious highlight), and I can’t wait for this weekend’s opening race in Bahrain.

I’m hardly unique in my burgeoning Formula 1 fandom, and “Drive to Survive” is the most commonly cited reason why. From The Athletic:

Formula One teams are fine-tuning their new cars right now in pre-season testing, but many fans will be thinking all about last year. That’s because season five of “Drive to Survive,” the Netflix docuseries, premieres Friday…At its heart remains the formula that not only made the show a global success but helped remake F1 in and for the United States by opening the high-speed drama, personalities and politics to everyone with a Netflix account…

That approach broke F1 away from its traditional older, male audience. Last year, a global survey by Motorsport Network found the average age of F1 fans — not just “Drive to Survive” viewers — had fallen from 36 to 32 since 2017. Female participation had doubled. “This has resonated with a different demographic, a younger demographic, a female demographic,” Ian Holmes, F1’s director of media rights, said in an interview last year. “Your avid fan will 100 percent hoover through the series. But what is particularly exciting for us is how non-fans have become fans.”

The shift in fan base even surprised Netflix. “The audience that Netflix thought was going to come and watch it was very different from the audience that has shown up,” Paul Martin, the executive producer of “Drive to Survive,” said at the Season Five premiere last week. (That was held in New York, another sign of the series’ significance in the United States.) “It’s reignited people’s passion for the sport, and has brought this whole new audience as well, which is just phenomenal.”

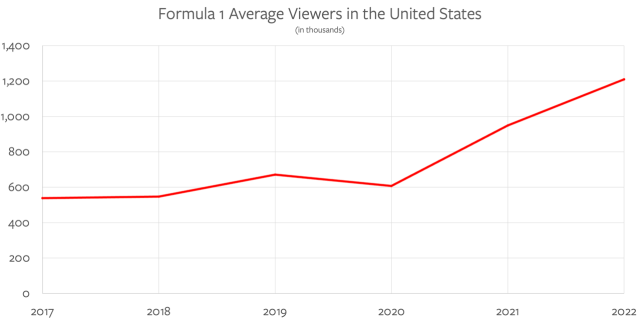

The U.S. viewership numbers tell the tale:

The first season of “Drive to Survive”, about the 2018 season, was released in 2019; the average number of U.S. viewers for a 2022 race was 121% higher than for the 2018 season. Of course Netflix doesn’t deserve all of the credit: Liberty Media, which acquired Formula 1’s commercial rights in 2017, has been pushing the sport to engage much more with fans, particularly in the United States, including a new race in Miami last year, and Las Vegas this year. To that end, I thought this portion of the 2023 rule changes was interesting; from Planet F1:

There has been a significant change in terms of the fan engagements drivers and teams are obligated to make with the introduction of two periods during a race weekend. On the Thursday, which is usually reserved for media and sponsorship duties, six drivers must be available for “fan engagement activities” which will last a maximum of 30 minutes. This will take place during a one-hour slot scheduled 20 hours and 30 minutes before the start of FP1. On the first day of track action, 10 drivers must similarity be available for the fan activities in a period that must finish at least 1.5 hours before FP1.

It is not just the drivers taking part either with three team principals per race also doing the same duties as the drivers. On the subject of team bosses, now four senior team reps have to be available for media each weekend, up from three, and must include the CEO, team principal and technical director as a minimum.

This is part of the deal: part of the brilliance of “Drive to Survive” is that it made everyone a star, from the most obscure midfield driver to team principals and CEOs; the powers-that-be in Formula 1 want to make sure they pay that off by not forgetting about the fans.

The NBA’s Missing Viewers

Formula 1 is, to be fair, still my side fling; the love of my sports life is basketball, particularly the NBA. Unfortunately, while my Milwaukee Bucks are doing fantastic — 14 straight wins as I write this — the NBA as a whole isn’t doing so hot. The previous weekend was the All-Star Game, the league’s pre-eminent regular season event, and the only thing worse than the desultory action on the floor was the ratings:

This isn’t a perfect apples-to-apples comparison: I’m comparing one event to a season-long average, we don’t yet have Formula 1’s 2023 numbers, and one chart is measured in thousands while the other is in millions. What is notable is that this decline is a fairly recent one; here are the All-Star viewership numbers going back to 2001:

The NBA Finals numbers are a bit noisier, because the popularity of the team and stars involved has a big impact on ratings; still, the last five years have plummeted as well (and last year’s Finals included big market teams Boston and Golden State, the latter of which pushed ratings to their highest post-Jordan levels last decade):

There are a whole host of potential explanations for this decline. The pandemic obviously had a massive effect, and some critics argue that the NBA pays too much attention to Twitter and not enough to normal fans. The most obvious explanation, though, is the long-awaited implosion of the pay-TV bundle.

Cable Cutting Calamity

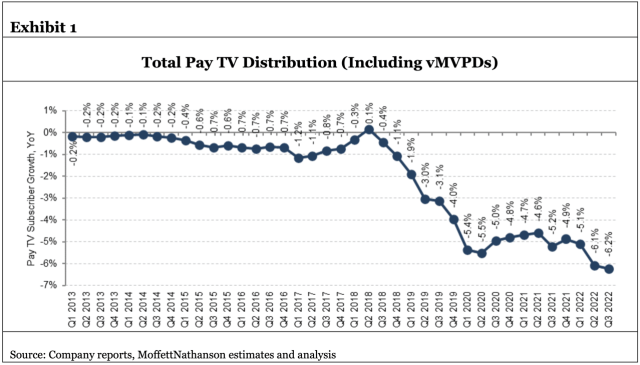

MoffettNathanson publishes a “Cord-Cutting Monitor” every few quarters; the most recent report was from Q3 2022, and things have been ugly for awhile now:

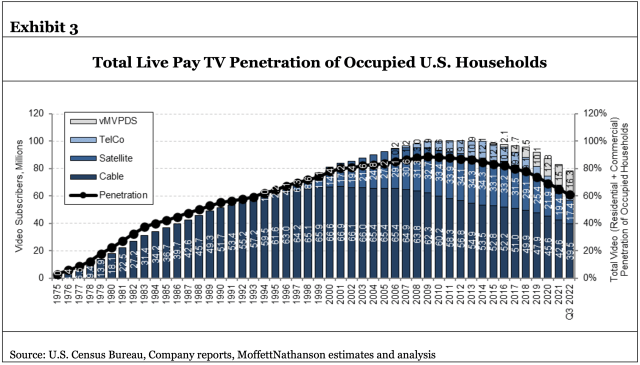

The result is that pay-TV has fallen from around 85% penetration and 100 million homes in 2011 to 60% penetration and 78 million homes last year:

What is notable is that this decline happened despite the rise in virtual pay-TV providers like YouTube TV:

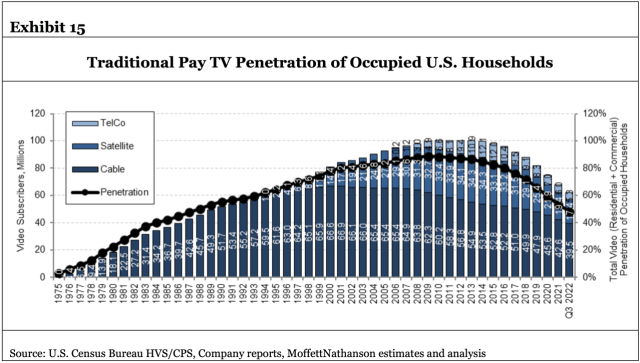

This means that the numbers for traditional pay-TV providers like cable are far worse:

The starting number is the same as the previous chart: 85% penetration and 100 million homes. The current state, though, is 48% penetration and 62 million homes.

The first observation to make about the NBA in the context of these numbers is that the league is almost exclusively on cable; the vast majority of games, including the All-Star game, are on ESPN or TNT, or a regional sports network. And, thanks to cord-cutting, there simply is a much smaller addressable market. This seems particularly important when it comes to an event like the All-Star game, which is much more likely to attract casual viewers who might have tuned in were the game available, but were never sufficiently invested in basketball to keep a pay-TV subscription.

What about the NBA Finals, though? Those are on ABC, which is broadcast over-the-air. That, though, requires having an antenna, the acquisition of which is more work than simply clicking a button. Moreover, if you haven’t watched the NBA all year, are you really going to care about the Finals? It is the biggest games of the year where the NBA reaps the highest ratings, but if interest was not sown throughout the year then the harvest may be smaller than hoped, particularly when it comes to the casual fans that drive the biggest ratings.

The Pay-TV Pinnacle

The three major American sports leagues by-and-large pre-dated TV: Major League Baseball has its roots in the formation of the National League in 1876; the National Football League started as the American Professional Football Conference in 1920, and the National Basketball Association was founded in 1946. The way the leagues made money was by selling tickets to fans, which meant that more games meant more tickets to sell, and thus more revenue. The brutal nature of the NFL has always kept its season relatively short (and its stadiums very large); MLB, though, plays a 162 game schedule, and the NBA an 82 game schedule.

Fast forward to 1976 and Ted Turner realized the burgeoning number of cable operators with satellite receivers were hungry for more channels; TBS became the first “superstation” — and second after HBO — to be broadcast nationally. TBS, though, needed inventory, and the Atlanta Braves baseball team and Atlanta Hawks basketball team provided a lot of it.

ESPN was founded three years later in 1979; originally the major sports leagues refused to sell their rights to anyone other than broadcast TV networks, but as ESPN’s penetration grew — thanks in large part to a groundbreaking deal to televise 8 NFL games in 1987 — the leagues became more amenable to the idea, and ESPN was more than willing to pay up, confident that more games would mean more carriage on cable providers because sports would drive new subscribers.

This set off a three-decade run of incredible profitability for the sports leagues and the cable channels that carried them: not only were games well-suited for advertising, but the emerging satellite industry provided an impetus for cable operators to pay ever increasing carriage fees for ESPN in particular, because sports fans cared enough to switch if they couldn’t get access to their favorite teams. Still, ESPN only had 24 hours in a day, which wasn’t enough to cover every game from every team; this led to the creation of regional sports networks whose primary purpose was to show every game in a team’s local market that wasn’t available nationally. Regional sports networks didn’t draw the biggest viewership totals, but their viewers were by definition the most committed and by extension the most willing to switch to see their favorite team, so their carriage fees continued to rise as well.

In short, by that 2011 peak, the sports leagues were at the peak of reaping the benefits from their massive slates of games: everyone paid for TV — well, 85% of the country, anyways — even though prices continues to rise, in large part because the leagues, and by extension the channels that carried them, kept raising their rates. The truth is that people like TV, even if they don’t like sports, and you either paid for everything or you got nothing.

Indeed, media companies leveraged this to their advantage, building corporate bundles within the larger cable bundles that were often anchored on sports: to get the entire collection of Disney channels distributors had to pay for ESPN, and vice versa; to get the NBA on TNT distributors had to pay for all of Warner Bros. channels. Broadcast networks were getting in on the act too via retransmission fees — carriage fees by another name, for all intents and purposes; Universal and 21st Century Fox’s collection of channels was bundled with the flagship broadcast network (NBC and Fox) and regional sports networks.

Sports wasn’t the only driver of rising prices: a particularly notable moment was AMC’s release of “Mad Men” in 2007; not that many people watched the show, but those who did really loved it — they were fans. That meant that AMC could suddenly start raising its carriage fees, particularly when it released the far more popular “The Walking Dead.” Soon everyone on cable was all-in on original content with the goal of increasing their carriage fees; this was the era of “Peak TV”.

And then came Netflix.

The Netflix Effect

Netflix has not, and may never, broadcast a live sporting event. The streaming service, though, is the ultimate driver of the decline from that 2011 peak, which means its impact on the sports landscape is profound.

Netflix is not some new phenomenon, of course. For the first half of the decade a Netflix subscription was something you obtained on top of your pay-TV subscription, and while pay-TV did start to lose a small number of subscribers — in part because Netflix was a willing buyer of all of those expensive TV shows from the Peak TV era — the decline was very gradual.

What changed over the last five years is that nearly the entire media company decided to compete with Netflix, instead of accommodate it. Competing with Netflix, though, meant attracting customers to sign up for a new service, instead of simply harvesting revenue from people who hooked up cable whenever they moved house, without a second thought. The former is a lot more difficult than the latter, which meant the media companies had to leverage their best stuff to attract customers: their most interesting new shows, and sometimes even their sports rights.

This had two big effects on pay-TV: first, customers who didn’t want to pay for sports and only ever signed up for pay-TV for TV shows had increasingly better alternatives via streaming, and second, pay-TV increasingly had little to offer other than sports. Matthew Ball explained the implications in a recent Stratechery Interview:

For the first time in pay-TV’s history, it got worse and that’s important. The price kept going up. Virtual MVPDs started jacking their rates up $10, $15 in a year, but for the first time content started getting harvested out. You had Paramount or at the time CBS say actually the sequel to “The Good Wife”, that’s only going to be on CBS All Access. You had Disney say we’re going to greenlight “The Mandalorian” and the Marvel series. That’s not going to go into linear, it’s only going to be on streaming. We had Paramount Global say actually “1923” that was going to debut on linear, now we’re going to put it on streaming. This kept happening. And in fact, just last year you had Disney take the 36th season of “Dancing with the Stars”, a show that had been on ABC, the broadcast network, for nearly 20 years, and they said it’s only going to be on Disney Plus.

And so for the first time, if you take a look over the last eighteen months, pay-TV penetration has imploded, because the product has gotten worse. For Peacock, NBCUniversal basically said, “Every high-quality show that we have in development for our broadcast network or our cable networks like USA isn’t even going to start there.” FX in 2019 announced that they were going to double their original programming hours. Then in 2020, Disney said, “Actually FX on Hulu is going to get half of that, it’s never going to show up on FX”. And by the way, everything that does appear on FX is going to be on Hulu twelve hours later with or without ads. There’s kind of no turning that around.

I asked Ball that question in the light of recent remarks by most media company executives this past quarter about renewing their focus on pay-TV, but as Ball noted, it is probably too late. In the long run it is Netflix, thanks to its subscriber base and relatively healthy capital structure, that will have the capability to pay for content media companies will have to sell to pay the bills, suggesting a potential future where Netflix is the primary distributor for everything but sports. And if this is true, the company will have won without televising sports, or even stepping foot on a soccer pitch, thanks to the media networks scoring an own goal by sacrificing pay-TV.

SuperFan and CasualFan

Shishir Mehrotra explains in the Four Myths of Bundling:

Imagine there are four products each delivered as a monthly subscription. We have a choice to deliver them each a-la-carte, or to produce a bundle across all of them. Now let’s divide the population for each good into 3 parts. Imagine that for each good, each prospective customer is one of these 3:

- SuperFan: This is someone who fits two criteria:

- They would pay the a-la-carte price for the channel. This means that they are fairly far along the price elasticity curve for the good (perhaps to the inelastic point)

- They have the activation energy to seek out the good and purchase it.

- CasualFan: Someone who would value the good if they had access to it, but lack one of the two SuperFan criteria ー either they aren’t willing to pay the a-la-carte price for the good, or don’t have the activation energy to seek it out, or both.

NonFan: Someone who will ascribe zero (or perhaps negative) value to having access to the good.

Here’s a quick visual:

If we offered these goods a-la-carte, then:

- The providers would only provide service (and collect revenue) from their SuperFans (the blue highlights), and

- Consumers would only have access to goods for which they are a SuperFan

The a-la-carte model clearly doesn’t maximize value, as consumers are getting access to fewer goods than they might be interested in, and providers are only addressing part of their potential market.

On the other hand, the bundled offer expands the universe and not only matches SuperFans with the products they are SuperFans of, but also allows for those consumers to get access to products of which they may be CasualFans. From a providers perspective, it gives access to consumers much beyond their natural SuperFan base. This is the heart of how bundles create value ー it’s not about addressing the SuperFan, it’s about allowing the CasualFan to participate.

SuperFans are still watching the NBA. NonFans probably were the first to cut the cord a decade ago. What has happened over the last five years is that CasualFans who care more about TV shows than they do sports — but might catch an All-Star or Finals game — no longer have any reason to subscribe to pay-TV for the reasons I just articulated. To put it another way, pay-TV has, as I predicted in 2017’s The Great Unbundling, become the sports and news bundle:

To put this concept in concrete terms, the vast majority of discussion about paid TV has centered around ESPN specifically and sports generally; the Disney money-maker traded away its traditional 90% penetration guarantee for a higher carriage fee, and has subsequently seen its subscriber base dwindle faster than that of paid-TV as a whole, leading many to question its long-term prospects.

The truth, though, is that in the long run ESPN remains the most stable part of the cable bundle: it is the only TV “job” that, thanks to its investment in long-term rights deals, is not going anywhere. Indeed, what may ultimately happen is not that ESPN leaves the bundle to go over-the-top, but that a cable subscription becomes a de facto sports subscription, with ESPN at the center garnering massive carriage fees from a significantly reduced cable base. And, frankly, that may not be too bad of an outcome.

I’m not too sure about that last sentence: ESPN does retain its pricing power, because it remains the most essential channel in the pay-TV bundle, but that is not because of programming like SportsCenter. It’s because it has live sports rights, and leagues are extracting higher and higher fees for those rights.

It used to be the case that sports leagues were not simply negotiating with ESPN; they were negotiating with all of Disney, and by extension, the cable bundle as a whole. All of those entities brought the sports leagues more casual fans:

- ESPN brought fans of other sports, and the extra publicity from SportsCenter.

- Disney brought fans of other Disney content.

- The cable bundle brought fans of all of the content in the world — and was the default choice for everyone.

This meant that everyone in the value chain could take a nice profit in line with their contribution to the overall bundle. Today, though, ESPN is in a much more vulnerable position:

- ESPN brings fans of other sports, but there is probably a lot of SuperFan overlap there; meanwhile SportsCenter is meaningless in a world of social media.

- Disney doesn’t bring anything; they put all of the good stuff on Disney+. This is exactly why Disney shareholders are pushing the company to spin out ESPN (which will become its own division): without the old pay-TV model there isn’t any real synergy between the businesses.

- The cable bundle brings other sports fans who still need TNT for the NBA and FS1 and the broadcast networks for the other sports.

There’s a big problem with that last point: those other sports channels are competing with ESPN for content, which drives up the price that much more, which is why ESPN lost the Big Ten. In short, the leagues are extracting nearly all of the profit from the value chain. That’s fine for now — and is why the NBA expects rights fees to go up again in its next deal — but the cracks are starting to show.

The RSN Canary

I mentioned the ultimate manifestation of harvesting above: regional sports networks. If I were to reproduce Mehrotra’s drawing above then regional sports networks would be the purple circle:

There just aren’t that many SuperFans of a single team, yet regional networks cost more than anything outside of ESPN — more in some markets. This worked in a world where everyone got cable by default, but remember that cable is losing far more customers than pay-TV as a whole, thanks to the rise of the aforementioned virtual pay-TV providers.

Virtual pay-TV providers don’t have a customer base to defend, or infrastructure costs to leverage: they distribute via the Internet that people already pay for. To that end, they don’t have to carry everything, and regional sports networks were the most obvious thing to drop: this lets virtual pay-TV providers have a lower price than cable by virtue of excluding content that most people don’t want.

This is the dynamic that explains the impending bankruptcy of Diamond Sports and Warner Bros. Discovery’s announcement that they would be cutting loose their regional sports networks or letting them go bankrupt as well. These networks negotiated rights deals with teams that presupposed getting money from far more subscribers than the number that retain cable subscriptions today; add in the amount of debt that Diamond Sports is carrying in particular and the numbers no longer make sense.

Note, though, that teams and leagues can’t just stream the games themselves, at least not economically. Consider a hypothetical region with 10,000 households:

- Diamond Sports may have assumed that they would collect $5/month from 70% of those households; that’s $35,000 a month.

- Instead Diamond Sports is collecting $5/month from 50% of those households; that’s $25,000 a month.

- However, only 5% of the households watch the regional sports network in question; for the team/league to earn $25,000 in revenue they would need to charge each viewer $50/month.

What happens at $50/month, though? Fewer viewers subscribe, which means the price that needs to be charged to the SuperSuperFans has to be even higher. Moreover, you make the sport completely inaccessible to CasualFans, which is a big problem for the long run.

This is why the outcome of the regional sports network drama will almost certainly be a renegotiation with the leagues for lower rights fees: the benefit of a bundle — even one as dramatically weakened as the cable TV bundle — is so extraordinary that it is in their best interest to earn less money with the system as it is instead of striking out alone.

This, though, is a reminder of just how misguided it was for all of these media companies to strike out on their own in streaming: they gave up easy money and a lot of it for the opportunity to build tech and customer service capabilities that they’re not particularly good at for the privilege of making their content less accessible. Not great!

Sowing vs. Reaping

The regional sports networks are also a cautionary tale for leagues focused on nothing but reaping revenue from the world as it was.2 The NBA benefits from its calendar — it’s the best inventory available for pay-TV from April to June in particular — and ESPN and TNT need content. At some point, though, if the audience becomes too small, the numbers could stop making sense.

This is where I come back to Formula 1: what impresses me about the sport from a business perspective is how hard it works to get new fans — it sows the seeds it later reaps. This ranges from “Drive to Survive” to new venues to even changing the rules to make sure fans get a chance to meet their heroes. This is the only way to survive in a media environment where you can’t simply reap the benefits of having lots of inventory for a bundle looking for content. Formula 1 has to earn its audience, particularly in the United States, and it is diligent about doing so.

The NBA, not so much. The league allows entertainment-killing nonsense like flopping and intentional fouling and endless timeouts and interminable reviews to continue, and refuses to shorten the season — increasing the importance of every game and making it more likely that star players play — for fear of losing gate revenue (and, until very recently, regional sports network revenue). Far too many players, meanwhile, seem to treat fans with derision, asking for trades or simply not trying, with seemingly zero appreciation that they are harvesting money that is downstream of structures put in place decades ago, which are rotting out as more and more CasualFans can’t be bothered to find an antenna, much less pay for cable.

The analogy, as with so many things in this digital era, is to newspapers. Newspapers used to make money not for their great journalism, but because they had a geographic monopoly on the cheap distribution of information; when distribution went to zero competition became infinite, and the only entities that profited were the Aggregators on one side and consumer-focused subscription-driven publishers on the other. The former filter the deluge of mostly crap free content, while the latter have to continually work to earn not just a reader’s attention but their money as well.

The NBA and other major sports are, to be clear, not newspapers: there is only one place you can watch LeBron James or Steph Curry or Giannis Antetokounmpo. Moreover, the pay-TV bundles still exists, and still needs inventory: RSN losses will likely be covered by national TV deal gains. It would behoove the league and its partners, though, particularly ESPN, to study companies and sports that don’t have as much differentiation or as many structural advantages. What would it mean to make the NBA far more fan-friendly? How much return might come from story-telling and myth-making instead of simply playing to Twitter?

The impact of the Internet on industry after industry, medium after medium, is to give customers choice: the entities that thrive work diligently to build a direct connection with customers and increase the attractiveness of the product, and the rest get ground up in the grist of Aggregation.